13. Flourishes

For the next piece I worked on we decided to do a slightly longer body of text, as this would pose a slightly different approach to laying out text. I also wanted to revisit the lowercase calligraphy I had done in an italic style. Charlotte had been given an oval piece of stone, what looked to be a pink marble. I was interested to work on this piece of stone, in part because I hadn’t carved marble before and working within a predefined shape posed a useful constraint.

We started by practicing the lower case round hand (foundational hand) lettering with parallel pens, specifically the Pilot parallel pens with ink cartridges, as opposed to dip pens, Fig. 1.

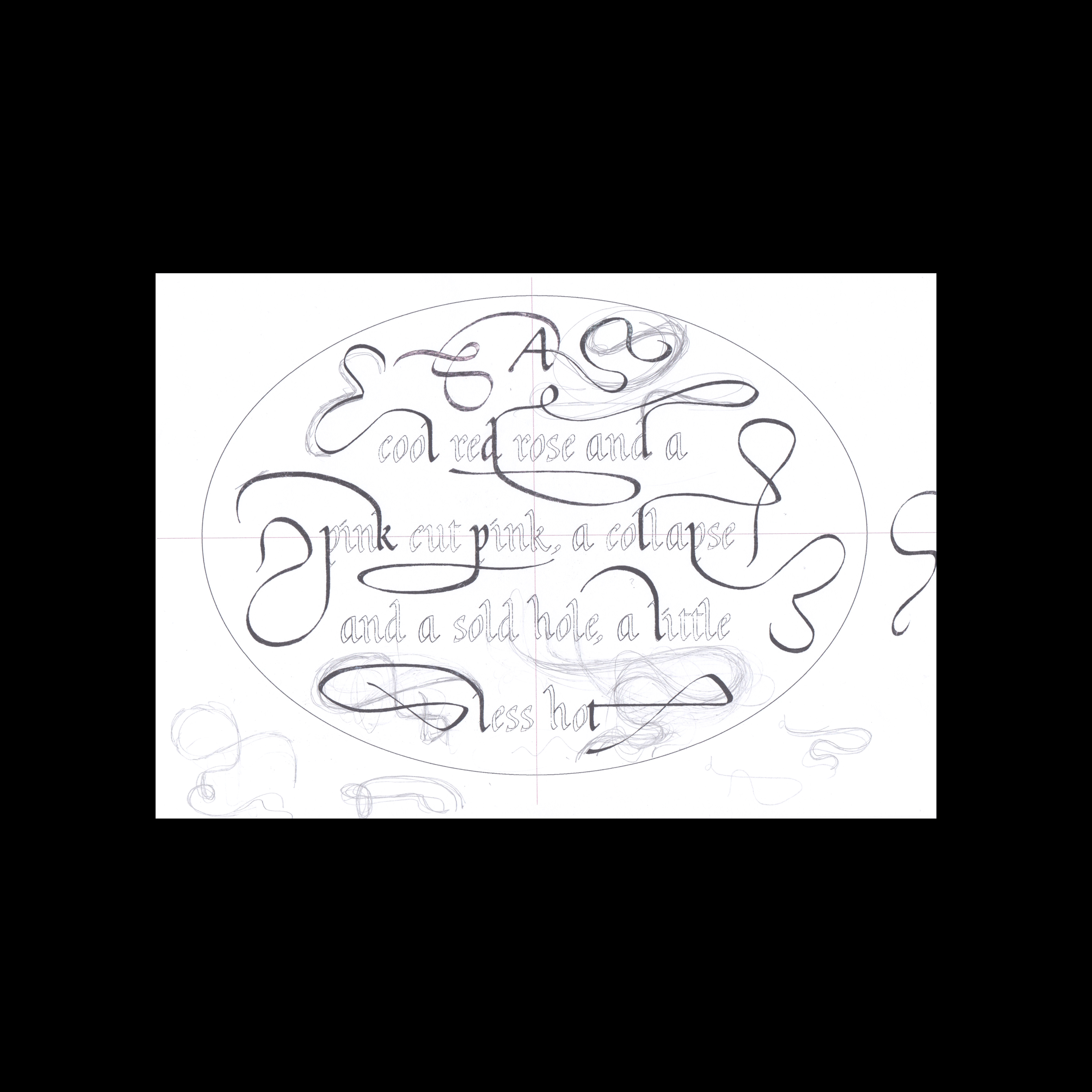

I had selected a four line poem by Gertrude Stein, ‘Red Roses’, not an overly long text, but a good length for the size of stone I had selected. As the stone was oval, I had thought a diamond shape for the text would work, however this left a lot of empty space around the text, Figs. 2-3, so I suggested incorporating flourishes into the design to fill the space.

Our starting point for flourishes was to look at David Kindersley’s and Lida Cardozo’s Letters Slate Cut. Charlotte had the original 1981 edition whilst I had a later 1990 edition. The two books have quite a different selection of works between editions, and whilst both have lots of examples of flourishes, the first edition has some very good ones. It became apparent from looking at the flourishes and trying to create them with a parallel pen that I was using the wrong tool, Fig. 4. I switched to a round brush and had more success with the weights and fluidity of movement, Fig. 5. This style of flourish did not entirely fit with the flat-edged pen letters that I had drawn so we looked further back into historic calligraphic examples to find a more appropriate language of flourishes.

Hardy Wilson describes the Humanistic hand as a move away from Gothic minuscules, but a reference to the Carolingian style of the 8th-10th Centuries, and that this 16th century letter is a precursor of the modern italic letterform. I found the slightly condensed and ‘spiky’ quality of the letters better suited the feel of the text, Fig. 6, so decided to continue with this letterform. The angle of the pen, being held at an 8-10° slant also lended the letters to extending better into flourishes than the round hand at 30-40°.

When I came back to Charlotte with my own compositional attempts, Fig. 8, she pointed out that certain letters and parts of letters are more suited to become a flourish, and that the most successful flourishes come out of the natural movement of the pen in the direction of the gesture. This was important to keep in mind as I developed the flourishes for this piece.

Due to my vertical layout of the text, I didn’t have a conducive number of letters with ascenders that could flow into flourishes, Fig. 10 shows how the flourishes weren’t really working, so I decided to flip the composition onto the horizontal, which actually worked much better.

To bring cohesion to the letterforms I needed to make some adjustments to what I had drawn with the pen, the characteristics are derived from the shape and width of the letter ‘o’, Fig. 11. I made mine narrower and slightly squared off, Fig. 12. From this I could then sketch out the letters and begin drawing out the text in their final ‘style’, Fig. 13.

In the process of working out the particulars of the letterforms I had drawn out the whole lowercase alphabet, Fig. 14. This seemed like a good oppertunity to use a piece of software that Charlotte had introducted me to, Fontshelf. An app that allows you to take a hand drawn alphabet and turn it into a typeface. In theory this would allow me to very easily adjust the spacing of the letters and quickly make changes. The app required a very clean and precise drawing of the letters that could be scanned in and cleaned up further on Photoshop and then imported. I actually did two versions, one as outlines and one with solid letters. This did indeed make it much easier to type out the letters and adjust the spacing. From there I had a full size version of the layout that I could incorporate the flourishes into, Fig. 15.

This process of drawing out the letter/flourish, scanning it and cleaning up the drawing was how I continued to amass the flourishes, and add them to the layout. It was really useful to see the whole design at scale and also to print out the design full size and work on flourishes that would precisely fit the design. The final design has essentially five large flourishes joining letters and fitting across the oval, see Fig. 28 below.

After I transferred the design onto the stone, Fig. 23, for this I did use copy paper, as the design was quite intricate, I then selected the placement of the mirror plates on the back so that they would interfere to the least extent with the design. Fig. 24 shows the placement of the mirror plates around the design. As the stone is fairly thin, 20mm and there are cracks running all over the stone, we didn’t want to run the risk of accidentally chipping a chunk out. I cut the holes for the mirror plates before I started carving the design, Fig. 25.