01 Trajan Alphabet

02 ‘torc’

03 Lowercase

04 ‘S’

05 Italics

06 Sign Writing

07 Low Relief

08 Nereids

09 Flourishes

10 ‘26 Connections’

11 Woodcarving

09 Flourishes

For the next piece I worked on we decided to do a slightly longer body of text, as this would pose a slightly different approach to laying out text. I also wanted to revisit the lowercase calligraphy I had done in an italic style. Charlotte had been given an oval piece of stone, what looked to be a pink marble. I was interested to work on this piece of stone, in part because I hadn’t carved marble before and working within a predefined shape posed a useful constraint.

![1]()

![2]()

![3]() We started by practicing the lower case round hand (foundational hand) lettering with parallel pens, specifically the Pilot parallel pens with ink cartridges, as opposed to dip pens, fig. 1. As a beginner I found the curve of the ’n’, which is also in the ‘m’, ‘a’, ‘h’, ‘u’, harder to achieve, in particular making that curve perfectly round as opposed to flattened and elongated it.

We started by practicing the lower case round hand (foundational hand) lettering with parallel pens, specifically the Pilot parallel pens with ink cartridges, as opposed to dip pens, fig. 1. As a beginner I found the curve of the ’n’, which is also in the ‘m’, ‘a’, ‘h’, ‘u’, harder to achieve, in particular making that curve perfectly round as opposed to flattened and elongated it.

I had selected a four line poem by Gertrude Stein, ‘Red Roses’, not an overly long text, but a good length for the stone I had selected. After drawing the text out in the shape it became apparent that breaking up the lines in a way that fitted the poem would create a lot of empty space around the text, figs. 2-3. I suggested the idea of incorporating flourishes into the design.

Our starting point for flourishes was to look at David Kindersley’s and Lida Cardozo’s Letters Slate Cut. Charlotte had the original 1981 edition whilst I had a later 1990 edition. The two books have quite a different selection of works between editions, and whilst both have lots of examples of flourishes, the first edition has some very good ones. It became apparent from looking at the flourishes and trying to create them with a parallel pen that I was using the wrong tool, fig. 4. I switched to a round brush and had more success with the weights and fluidity of movement, fig. 5. This style of flourish did not entirely fit with the flat-edged pen letters that I had drawn so we looked further back into historic calligraphic examples to find a more appropriate language of flourishes.

![4]()

![5]()

![6]() Whilst thinking about flourishes made with a flat edged pen, it became apparent that the rounded letterform I had been drawing wasn’t quite right either.

This lead me to The Encyclopaedia of Calligraphy Techniques by Diana Hardy Wilson and her example of a Humanistic style of lettering. Hardy Wilson describes the Humanistic hand as a move away from Gothic minuscules, but a reference to the Carolingian style of the 8th-10th Centuries, and that this 16th century letter is a precursor of the modern italic letterform. I found the slightly condensed and ‘spiky’ quality of the letters better suited the feel of the text, fig. 6, so decided to continue with this letterform. The angle of the pen, being held at an 8-10° slant also lended the letters to extending better into flourishes than the round hand at 30-40°.

Whilst thinking about flourishes made with a flat edged pen, it became apparent that the rounded letterform I had been drawing wasn’t quite right either.

This lead me to The Encyclopaedia of Calligraphy Techniques by Diana Hardy Wilson and her example of a Humanistic style of lettering. Hardy Wilson describes the Humanistic hand as a move away from Gothic minuscules, but a reference to the Carolingian style of the 8th-10th Centuries, and that this 16th century letter is a precursor of the modern italic letterform. I found the slightly condensed and ‘spiky’ quality of the letters better suited the feel of the text, fig. 6, so decided to continue with this letterform. The angle of the pen, being held at an 8-10° slant also lended the letters to extending better into flourishes than the round hand at 30-40°.

![7]()

![8]()

One piece in-particular that stood out to me from Letters Slate Cut, and which I kept in mind throughout working on this piece, was a lowercase italic alphabet by David Kindersley, shown above in fig. 7. The flourishes go around the edge of the body of text, but also through the letters, crossing lines, navigating around the entire piece, from top to bottom. This piece really highlights how the flourish can be used to get from one point to another but not in a straightforward way. I particularly liked the connection between the ‘d’ and the ‘j’ on the line below, which in turn jumps up though the dot of the ‘j’ to the top of the ‘f’, itself nestled in the ‘b’. The flourishes in this piece were less lines to be followed and more an overall texture that is part of the visual rhythm of the text. This example really shows flourishes at their most complicated yet effortless.

When I came back to Charlotte with my own attempts, fig. 8, she pointed out that certain letters and parts of letters are more suited to become a flourish, and that the most successful flourishes come out of the natural movement of the pen in the direction of the gesture. This was important to keep in mind as I developed the flourishes for this piece. Owing to my layout I had fewer letters with ascenders on the edges that could create a flourish from, and more descending strokes which wouldn’t naturally flow into a flourish.

![9]()

![10]()

![11]()

At this point, I had decided on the letter forms I wanted to develop and was slightly more familiar with flourishes. The next stage was to move away from the flat edged pen and start drawing the letters with a pencil. Redrawing and altertering the letterforms slightly would also make them more appropriate for carving.

To bring cohesion to the letterforms the shapes needed to derive from the ‘o’ and fit into the width of that letter, fig. 9 show the development away from the pen drawn ‘o’ to a carvable version. In the pen version of the letters, the ‘o' was quite different, much too round to fit with the other letters, as shown in fig. 10. So I needed to go back and adjust the ‘o’ in a way to fit with the rest of the letters. From this I could then sketch out a whole alphabet and begin drawing out my letter forms in their final ‘style’, fig. 11 shows the final letterform coming together.

![12]()

![13]() Looking through Charlotte’s books on calligraphy, The Universal Penman, an exhibition catalogue from the Victoria and Albert Museum from 1980, had a huge range of calligraphic examples and lots of different types of flourishes that were clearly made with a flat edged pen. One piece in particular stood out to me, a page from Giovanni Antonio Tagliente’s book The True Art of Excellent Writing or Lo presente libro, a writing manual, fig. 12. I subsequently found that the full book is available to view and download as a PDF on the Library of Congress website, for anyone interested.

Looking through Charlotte’s books on calligraphy, The Universal Penman, an exhibition catalogue from the Victoria and Albert Museum from 1980, had a huge range of calligraphic examples and lots of different types of flourishes that were clearly made with a flat edged pen. One piece in particular stood out to me, a page from Giovanni Antonio Tagliente’s book The True Art of Excellent Writing or Lo presente libro, a writing manual, fig. 12. I subsequently found that the full book is available to view and download as a PDF on the Library of Congress website, for anyone interested.

After working on flourishes for a few days I realised and decided that I may need to flip the composition from vertical to horizontal in order to better accommodate the flourishes that I was trying to achieve, fig. 13 shows how the flourishes weren’t really working. This turned out to be a good idea.

![14]()

![15]()

At this point I had drawn out the whole lowercase alphabet whilst working out the details, fig. 14. This seemed like a good oppertunity to use a piece of software that Charlotte had introducted me to, Fontshelf. An app that allows you to take a hand drawn alphabet and turn it into a typeface. In theory this would allow me to very easily adjust the spacing of the letters and quickly make changes. The app required a very clean and precise drawing of the letters that could be scanned in and cleaned up further on Photoshop and then imported. I actually did two versions, one as outlines and one with solid letters. This did indeed make it much easier to type out the letters and adjust the spacing. From there I had a full size version of the layout in Illustrator that I could incorporate the flourishes into, fig. 15.

![16]()

![17]()

![18]()

As I started to draw types of flourishes seen in Lo presente libro I started to understand how certain shapes were generated, through twisting, pulling and pushing the pen. That the direction you were moving the pen in created quite specific shapes, that weren’t possible if you tried to draw them in another way.

I began a very slow process of drawing shapes that would link letters and traverse empty space whilst twisting and changing direction in a flowing way. Figs. 16-18 show the developement of inital pen drawn line, to adjusted pencil sketch then placed in the composition. At first I saw this piece as a way to show the different types of flourish I had found, a single letter having a large ornate flourish. However this lended a un-cohesive look to the composition and it also left spaces where I struggled to accommodate a flourish. This led me to begin to join letters, from one line to the next with a flourish. It became clear that if some parts were joint then perhaps all of them should be. I was also aware of the symmetry might help bring the piece together that I was resisting. As with the Kindersley example where there are similar shapes, but not identical that tie the composition together.

This process of drawing out the letter/flourish, scanning it and cleaning up the letterform was how I continued to amass the flourishes and add them to the layout of text I already had. It was really useful to see the whole design at scale and also to print out the design full size and work on flourishes that would precisely fit the design. The final design shows the flourishes fitting almost into four quarters across the oval. Although perhaps slightly unfarmiliar as far as flourishes go, I think as the outcome of a process of learning they sit well on the piece.

![19]()

![20]()

![21]()

![22]()

Once I had the design finalised, I moved on to shaping the stone. The stone was an oval, but not a symmetrical one and slightly squared. We decided to cut down the edges to create a nicer shape, fig. 19 shows the design laid over the stone and the edges to be cut away. For this I cut away the stone by hand rather than using electric tools. Although it takes longer this was a good opportunity to put into practise the skills I had learnt over the last year and to familiarise myself with carving this stone. Figs. 20-22 show the process of carving away and polishing the surfaces.

![23]()

![24]()

![25]()

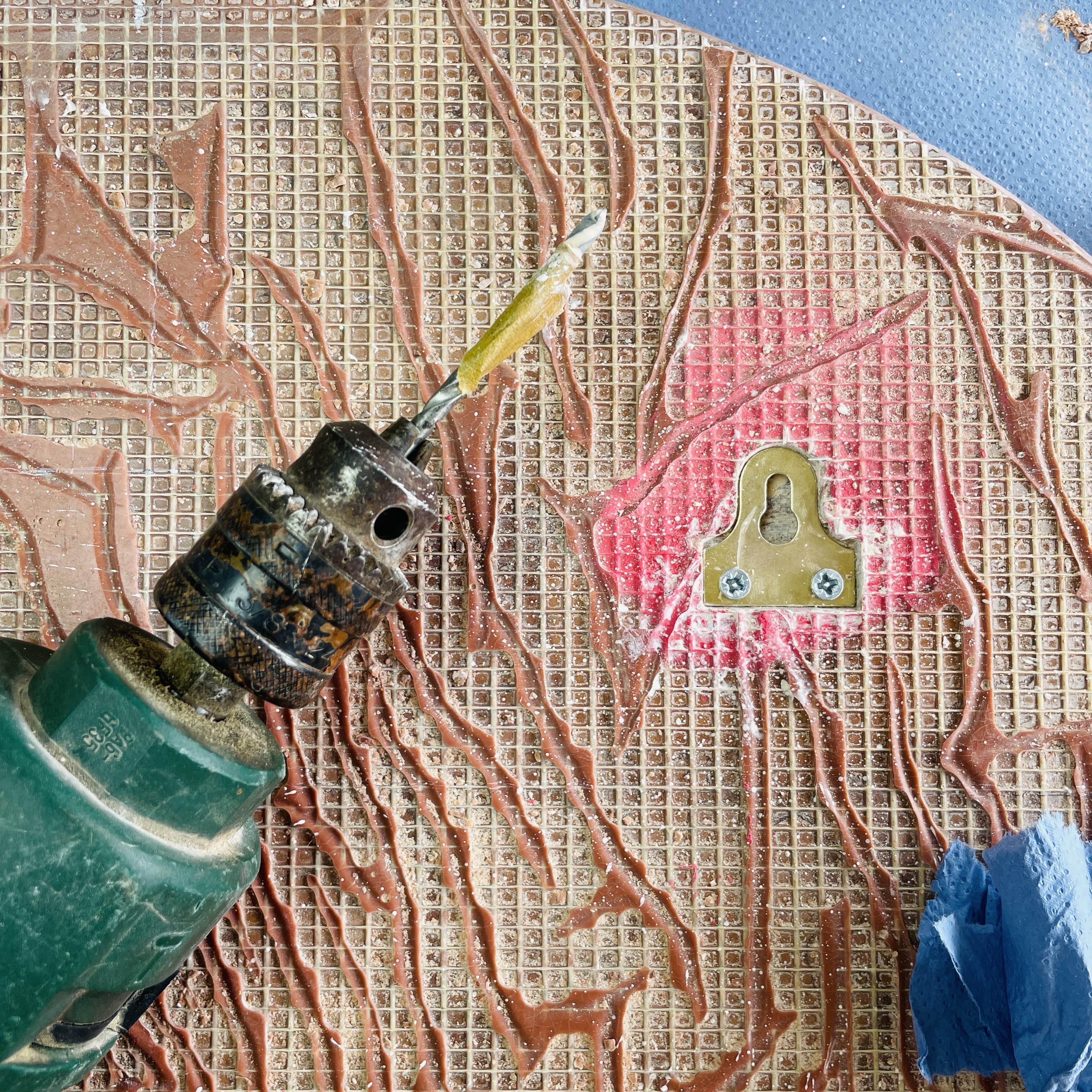

After I transferred the design onto the stone, fig. 23, for this I did use copy paper, as the design was quite intricate, I then selected the placement of the mirror plates on the back so that they would interfere to the least extent with the design. Fig. 24 shows the placement of the mirror plates around the design. As the stone is fairly thin, 20mm and there are cracks running all over the stone, we didn’t want to run the risk of accidentally chipping a chunk out. I cut the holes for the mirror plates before I started carving the design, fig. 25.

![26]()

![27]()

I then began caving. It quickly became apparent that certain aspects of the design would prove fiddly to carve, specifically the curve at the top and bottom of the uprights into the serif, as can be seen in fig. 26, the top and bottom of the ‘c’, the curve in the ‘u’ and ‘t’. The carving probably took me a few weeks in total, fitting around other work.

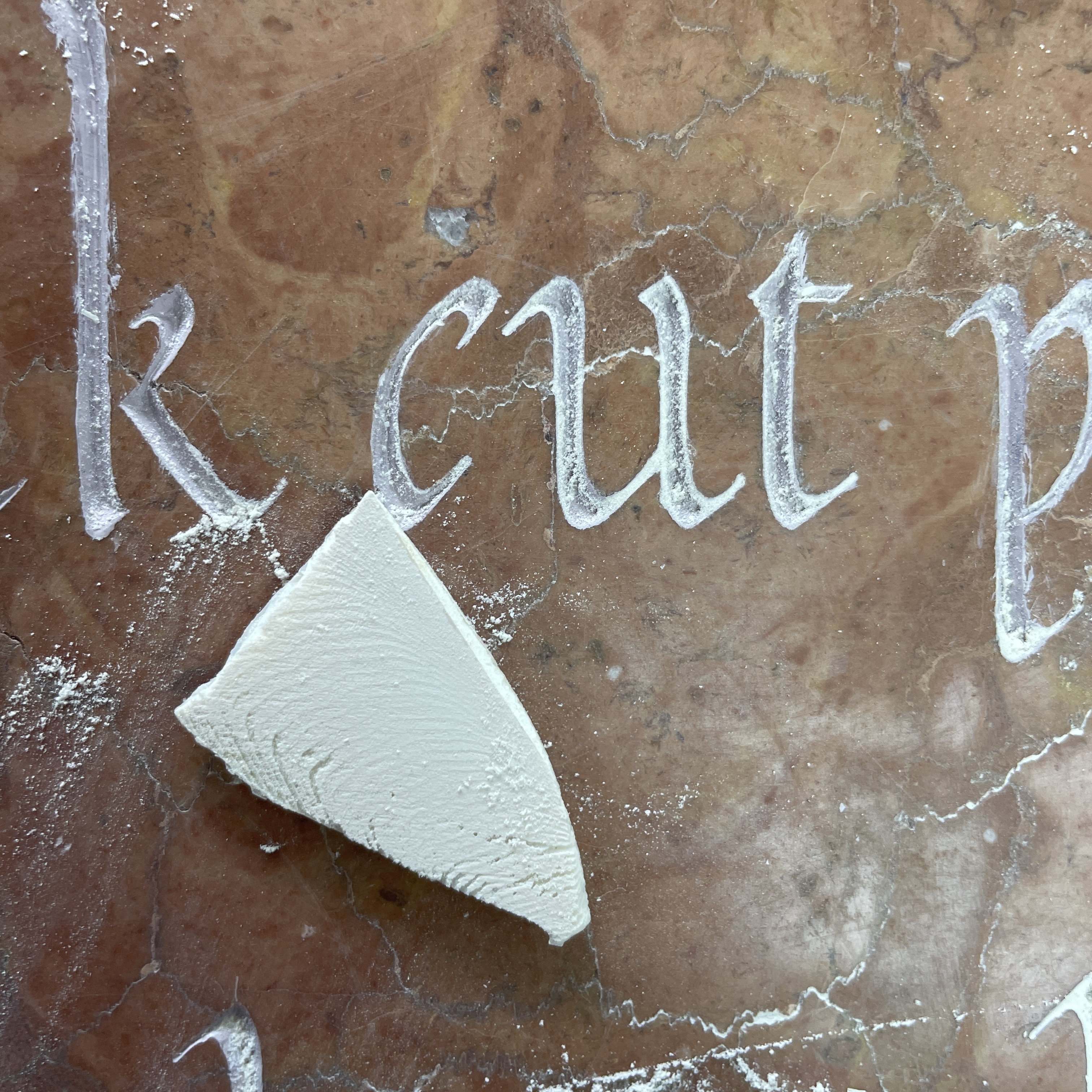

Upon finishing the carving we painted the letters with a mix of sign writers paint and oil paint. I tried to match the colour of the stone dust, but a little lighter so that the letters ‘pop’ out. I ended up doing two layers of paint to be sure that I’d covered all cracks. To remove any paint that was left over the edges of the letters we used a cuttlefish bone, fig. 27, which is a mild abrasive and leaves a nicely buffed finish. It works well on a stone that can be polished, such as marble. Figs. 28-29 shows the finished piece.

![28]()

![29]()

References

‘Red Roses’ from Tender Buttons, Gertrude Stein, Uniformbooks, Axminster, 2012

02 ‘torc’

03 Lowercase

04 ‘S’

05 Italics

06 Sign Writing

07 Low Relief

08 Nereids

09 Flourishes

10 ‘26 Connections’

11 Woodcarving

09 Flourishes

For the next piece I worked on we decided to do a slightly longer body of text, as this would pose a slightly different approach to laying out text. I also wanted to revisit the lowercase calligraphy I had done in an italic style. Charlotte had been given an oval piece of stone, what looked to be a pink marble. I was interested to work on this piece of stone, in part because I hadn’t carved marble before and working within a predefined shape posed a useful constraint.

I had selected a four line poem by Gertrude Stein, ‘Red Roses’, not an overly long text, but a good length for the stone I had selected. After drawing the text out in the shape it became apparent that breaking up the lines in a way that fitted the poem would create a lot of empty space around the text, figs. 2-3. I suggested the idea of incorporating flourishes into the design.

Our starting point for flourishes was to look at David Kindersley’s and Lida Cardozo’s Letters Slate Cut. Charlotte had the original 1981 edition whilst I had a later 1990 edition. The two books have quite a different selection of works between editions, and whilst both have lots of examples of flourishes, the first edition has some very good ones. It became apparent from looking at the flourishes and trying to create them with a parallel pen that I was using the wrong tool, fig. 4. I switched to a round brush and had more success with the weights and fluidity of movement, fig. 5. This style of flourish did not entirely fit with the flat-edged pen letters that I had drawn so we looked further back into historic calligraphic examples to find a more appropriate language of flourishes.

One piece in-particular that stood out to me from Letters Slate Cut, and which I kept in mind throughout working on this piece, was a lowercase italic alphabet by David Kindersley, shown above in fig. 7. The flourishes go around the edge of the body of text, but also through the letters, crossing lines, navigating around the entire piece, from top to bottom. This piece really highlights how the flourish can be used to get from one point to another but not in a straightforward way. I particularly liked the connection between the ‘d’ and the ‘j’ on the line below, which in turn jumps up though the dot of the ‘j’ to the top of the ‘f’, itself nestled in the ‘b’. The flourishes in this piece were less lines to be followed and more an overall texture that is part of the visual rhythm of the text. This example really shows flourishes at their most complicated yet effortless.

When I came back to Charlotte with my own attempts, fig. 8, she pointed out that certain letters and parts of letters are more suited to become a flourish, and that the most successful flourishes come out of the natural movement of the pen in the direction of the gesture. This was important to keep in mind as I developed the flourishes for this piece. Owing to my layout I had fewer letters with ascenders on the edges that could create a flourish from, and more descending strokes which wouldn’t naturally flow into a flourish.

At this point, I had decided on the letter forms I wanted to develop and was slightly more familiar with flourishes. The next stage was to move away from the flat edged pen and start drawing the letters with a pencil. Redrawing and altertering the letterforms slightly would also make them more appropriate for carving.

To bring cohesion to the letterforms the shapes needed to derive from the ‘o’ and fit into the width of that letter, fig. 9 show the development away from the pen drawn ‘o’ to a carvable version. In the pen version of the letters, the ‘o' was quite different, much too round to fit with the other letters, as shown in fig. 10. So I needed to go back and adjust the ‘o’ in a way to fit with the rest of the letters. From this I could then sketch out a whole alphabet and begin drawing out my letter forms in their final ‘style’, fig. 11 shows the final letterform coming together.

After working on flourishes for a few days I realised and decided that I may need to flip the composition from vertical to horizontal in order to better accommodate the flourishes that I was trying to achieve, fig. 13 shows how the flourishes weren’t really working. This turned out to be a good idea.

At this point I had drawn out the whole lowercase alphabet whilst working out the details, fig. 14. This seemed like a good oppertunity to use a piece of software that Charlotte had introducted me to, Fontshelf. An app that allows you to take a hand drawn alphabet and turn it into a typeface. In theory this would allow me to very easily adjust the spacing of the letters and quickly make changes. The app required a very clean and precise drawing of the letters that could be scanned in and cleaned up further on Photoshop and then imported. I actually did two versions, one as outlines and one with solid letters. This did indeed make it much easier to type out the letters and adjust the spacing. From there I had a full size version of the layout in Illustrator that I could incorporate the flourishes into, fig. 15.

As I started to draw types of flourishes seen in Lo presente libro I started to understand how certain shapes were generated, through twisting, pulling and pushing the pen. That the direction you were moving the pen in created quite specific shapes, that weren’t possible if you tried to draw them in another way.

I began a very slow process of drawing shapes that would link letters and traverse empty space whilst twisting and changing direction in a flowing way. Figs. 16-18 show the developement of inital pen drawn line, to adjusted pencil sketch then placed in the composition. At first I saw this piece as a way to show the different types of flourish I had found, a single letter having a large ornate flourish. However this lended a un-cohesive look to the composition and it also left spaces where I struggled to accommodate a flourish. This led me to begin to join letters, from one line to the next with a flourish. It became clear that if some parts were joint then perhaps all of them should be. I was also aware of the symmetry might help bring the piece together that I was resisting. As with the Kindersley example where there are similar shapes, but not identical that tie the composition together.

This process of drawing out the letter/flourish, scanning it and cleaning up the letterform was how I continued to amass the flourishes and add them to the layout of text I already had. It was really useful to see the whole design at scale and also to print out the design full size and work on flourishes that would precisely fit the design. The final design shows the flourishes fitting almost into four quarters across the oval. Although perhaps slightly unfarmiliar as far as flourishes go, I think as the outcome of a process of learning they sit well on the piece.

Once I had the design finalised, I moved on to shaping the stone. The stone was an oval, but not a symmetrical one and slightly squared. We decided to cut down the edges to create a nicer shape, fig. 19 shows the design laid over the stone and the edges to be cut away. For this I cut away the stone by hand rather than using electric tools. Although it takes longer this was a good opportunity to put into practise the skills I had learnt over the last year and to familiarise myself with carving this stone. Figs. 20-22 show the process of carving away and polishing the surfaces.

After I transferred the design onto the stone, fig. 23, for this I did use copy paper, as the design was quite intricate, I then selected the placement of the mirror plates on the back so that they would interfere to the least extent with the design. Fig. 24 shows the placement of the mirror plates around the design. As the stone is fairly thin, 20mm and there are cracks running all over the stone, we didn’t want to run the risk of accidentally chipping a chunk out. I cut the holes for the mirror plates before I started carving the design, fig. 25.

I then began caving. It quickly became apparent that certain aspects of the design would prove fiddly to carve, specifically the curve at the top and bottom of the uprights into the serif, as can be seen in fig. 26, the top and bottom of the ‘c’, the curve in the ‘u’ and ‘t’. The carving probably took me a few weeks in total, fitting around other work.

Upon finishing the carving we painted the letters with a mix of sign writers paint and oil paint. I tried to match the colour of the stone dust, but a little lighter so that the letters ‘pop’ out. I ended up doing two layers of paint to be sure that I’d covered all cracks. To remove any paint that was left over the edges of the letters we used a cuttlefish bone, fig. 27, which is a mild abrasive and leaves a nicely buffed finish. It works well on a stone that can be polished, such as marble. Figs. 28-29 shows the finished piece.

References

‘Red Roses’ from Tender Buttons, Gertrude Stein, Uniformbooks, Axminster, 2012